Twenty-five years ago I penned this piece on the origins of barbecue-style cooking. I pitched it to a variety of magazines, all of which passed with similar responses: ‘…not enough current interest in the barbecue topic…’ Well, I’m pretty certain that’s changed.

The origin of barbecue-style cooking is almost as hotly a debated topic as “which region, state, or city produces the best barbecue”. Texans, Kansans, Alabamans, and Carolinians are arguably (and believe me, the barbecue experts love to argue) all great contributors, but none of them are the originators.

It is likely that barbecuing had multiple origins. Undoubtedly, the first barbecue took place not long after Peking man (Homo Erectus, predecessor to Homo Sapiens) discovered fire (sometime between 400,000 and 500,000 BC) and accidentally dropped a piece of woolly mammoth thigh into the blaze (although it appears from artifacts found in his caves that he may have had a preference for venison). After fishing the meat out of the fire with a stick (perhaps this is when the fork was invented?) he discovered that it was easier to tear apart, and chew, and—by-golly, it tasted better too!

There is some speculation regarding Mongolian barbecuing, practiced as far back as the 13th Century. While Genghis Khan’s army was on the move, conquering North China or Turkestan, they would cook their meals on their shields in an open fire. This seems closer to wok cooking than traditional barbecue, however.

The earliest traceable origins of barbecue, as we know it today, point to the Arawak Indians, or their rivals—the cannibalistic Carib Indians (no telling what they had on the rotisserie), both indigenous to the Caribbean Islands. The word “barbecue” is derived from “barbacoa”, the Spanish version of a Taino (the Arawak Indian language) word that refers to a rack for holding meat over an open fire.

The French have tried to claim that their expression “barbe-a-queue” points to France as the origin of barbecue. It means “from beard to tail”, which they claim relates to cooking the entire animal. But I could find no historical references to France having had anything to do with the invention or progression of barbecue-style cooking. However, French pirates, in the Caribbean, may have contributed to it.

There are substantial references to barbecuing’s Caribbean ancestry, and it is a colorful ancestry at that. The island of Hispaniola, now shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic, was owned by the Spanish, from 1492 when Columbus first ran into it, until 1795. In the early 1600’s it became a refuge for French, English, and Dutch vagabonds and escaped criminals, much to the chagrin of Spain. From the local Indians, these refugees learned to butcher and cook the cattle and boar that were plentiful on Hispaniola. The cooking method was called “boucan”—a French variation of the aforementioned Taino term for smoke-drying and cooking meat on a “barbacoa” rack. Preparing and selling the meat to ships that stopped on Hispaniola became the refugees’ primary vocation. They became known as “boucaniers”, a label that eventually evolved into “buccaneers”. Providing provisions was apparently too legitimate a livelihood for these scalawags and they soon took to invading any ship that belonged to their arch-nemesis Spain. One of the last and most famous of the buccaneers was Sir Henry Morgan who, with his army of pirates, The Brethren of the Coast, sacked Puerto Principe, Porto Bello, Maracaibo and Panama City, Panama among others. England eventually named him Lieutenant-Governor of Jamaica.

At this point I will indulge in some speculation that is bound to raise controversy. I think that since pirates frequented both the east and west coasts of Florida, it seems quite possible that the first barbecues on mainland American soil could have been held in Florida.

One thing is certain. Regardless of where it originated, barbecue is now American cuisine! Its evolution and development have taken place in America.

Barbecue flavoring had practical beginnings. At first, seasoning the meat was a way to preserve it, not flavor it. Since there was no refrigeration, the Arawaks and Caribs coated meat with spices and marinades to keep it from spoiling so quickly. African slaves brought to the Caribbean in the 17th and 18th Century learned the seasoning and barbecuing technique from the Indians, added some spices of their own, and later brought that knowledge to America. As early as the mid-1600’s there are written accounts of colonists in Virginia conducting all-day pig roasts, using brick-lined pits dug into the ground. Since large quantities of meat were cooked at a time, barbecues became a social gathering event. Eventually it became a main attraction at political rallies.

What is probably more important than where barbecue originated, is where and how it evolved and where it has been perfected. This is where fervent opinions fly. Defenders of their region’s barbecue invariably claim that theirs is the only barbecue worth eating.

Each region or locale for which a style is named has distinguishing characteristics. Texas-style is typically beef brisket with a sauce made from ketchup, onions, brown sugar, cayenne pepper, and chili powder. Alabama-style is chopped pork with a spicy ketchup and vinegar (and sometimes mustard) sauce. Some styles are so specific that they are associated with a city, rather of an entire state or region. Kansas City, Memphis, and Lexington, North Carolina are considered by many aficionados to be the Emerald Cities of barbecue.

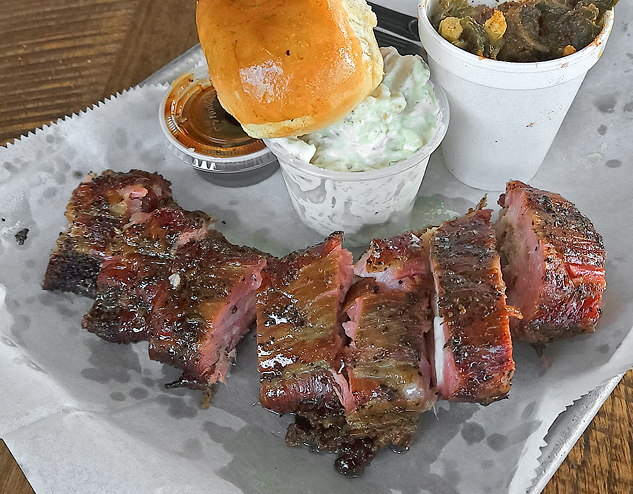

One of the most distinctive is Lexington-style barbecue. In 1983 the North Carolina General Assembly designated Lexington as the “Hickory-Cooked Barbecue Capital of the Piedmont”. They slow-smoke pork shoulder for half a day over a hickory (and sometimes oak) fire, in a brick pit. Seasoned only with a little salt, the meat is kept at around 180 degrees; resulting in very juicy, tender pork. It is then pulled apart and chopped into bite-sized chunks, or minced into a “hash” consistency. You can even specify “outside brown” and they will chop up more of the charred, crusty, tasty, outer part of the meat for you. Lexington sauce is unique among barbecue sauces. The primary ingredient is white vinegar with crushed red pepper and ground black pepper, a little salt and garlic and just enough ketchup to give it a red tint. Lexington-style pork is usually eaten with vinegary coleslaw, that when mixed with the meat, gives the whole concoction a tangy flavor.

True barbecue connoisseurs are on a never-ending cuisine quest—the search for the best barbecue. The endeavor takes on religious proportions—not unlike searching for the Holy Grail. Everyone has their favorite styles, but the truth is no one can prove one barbecuing technique, style, sauce, or choice of meat better than another. Good taste is on the tongue of the beholder.

An afterthought, postscript: This isn’t a scientifically quantified observation but it seems to me that half the BBQ joints I’ve run across feature a smiling, dancing, or otherwise exuberantly happy pig as a mascot on their sign. I don’t get it—doesn’t the pig know?

Bruce Hunt